Too many of Maine’s promising start-up companies struggle with the “ditch of death”. That’s the gap that opens up somewhere around when a vision has manifested into some version of a sellable product and when the founding team has enough customer knowledge to grow organically or attract external, private capital.

But Maine is not unique in this regard. There is a popular meme stating that 9 out of 10 start-ups will fail. Harvard Business School says it is 3 out of 4. The true statistic is subject to many complexities and nuances that are being benchmarked by well-known groups like the Kauffman Foundation, National Venture Capitalists Association, and new approaches like Startup Compass or CB Insights.

Regardless which sector you are talking about, or whether the team has experience, external funding, etc. – it is hard to argue that Maine, along with the rest of the country, needs more successful startups.

So how can the Maine Technology Institute and the start-up ecosystem we are a part of in Maine do a better job helping our early-stage stars?

The 20th Century StartUp Process Gets an Upgrade

Over the past decade, there have been a few important shifts in the start-up landscape.

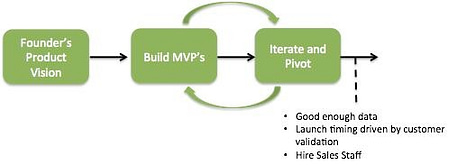

First, the cost to create many products and services continues to decline. New approaches to prototyping alpha/beta stage offerings have dramatically reduced costs and product time to market. As an Entrepreneur in Residence, I have seen the agile product development concepts popularized in The Lean Start-Up being adopted en masse in our portfolio companies. From where I sit, the Maine start-up ecosystem is on par with other markets in its embrace of the new approach to product research + development.

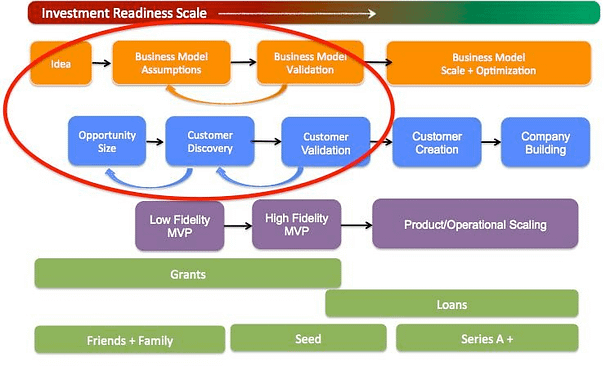

Next, there is a growing acknowledgment that start-ups are in SEARCH of a business model, NOT executing on one. While that statement may seem obvious to some, it is a distinction with a difference – particularly in process – because the Maine start-up ecosystem is behind in operationalizing this approach.

Let me explain while stealing heavily from Steve Blank of Stanford University. In the 20th century the yellow brick road a startup typically followed looked like this:

A founder would write a business plan filled with assumptions and go pitch it. Somewhere along the way, this plan – mostly written for external audiences – went from a vision backed by a set of assumptions to something more like an internal operating plan. The catch with this shift is that companies will often scale costs prematurely before validating their assumptions about the customer and the market. Over the last 10+ years, pull marketing has met agile product development and the entire start-up process got an upgrade.

A founder would write a business plan filled with assumptions and go pitch it. Somewhere along the way, this plan – mostly written for external audiences – went from a vision backed by a set of assumptions to something more like an internal operating plan. The catch with this shift is that companies will often scale costs prematurely before validating their assumptions about the customer and the market. Over the last 10+ years, pull marketing has met agile product development and the entire start-up process got an upgrade.

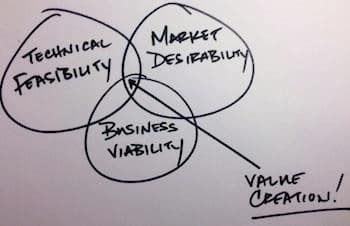

In this approach, the founding team writes a plan with a heavy emphasis on surfacing the key assumptions about the business model and establishing a critical path to testing them. At each step of the way the team is learning about the market, the customer and what will give them “unfair competitive advantage”. By the time a start-up following this approach gets to launch spending levels (aka scaling up), they have dramatically reduced market adoption risk – the key risk for most start-ups in the 21st century.

In this approach, the founding team writes a plan with a heavy emphasis on surfacing the key assumptions about the business model and establishing a critical path to testing them. At each step of the way the team is learning about the market, the customer and what will give them “unfair competitive advantage”. By the time a start-up following this approach gets to launch spending levels (aka scaling up), they have dramatically reduced market adoption risk – the key risk for most start-ups in the 21st century.

Validating the 21st-century process

In 2011 the NSF decided it had had enough of its struggles with the ditch of death when it created its Innovation Corps – with the sole purpose of increasing the number of government-funded innovations that succeed. They created a 10-week program in partnership with Stanford University that took promising teams (comprised of a top researcher a top scientist and an experienced business partner) through a step-wise process to systematically test the assumptions in their business models.

As of this year, 11 major universities are partnered in the ICorps program and over 400 teams (across multiple industries) have participated. For the curious, there are regular updates on individual case studies and the program overall here.

One the most impressive statistics reported thus far is that classes have tested an average of 36 business model hypothesis each and invalidated 45% of them within the first 8 weeks. That bears repeating…on average, 45% of the assumptions in the models that these promising teams brought in were incorrect in some way and they learned that in a fraction of the time they might have, were it not for the rigorous application of the scientific method to the business model process.

What Are We Missing In Maine?

We have a lot of things going for us in Maine. We have inventors, scientists, developers, and tinkerers all with loads of grit and determination. We have a growing start-up ecosystem populated by creative players like MECD, Maine Start Up & Create Week, Maine Angels, The Maine Venture Fund, Blackstone Accelerates Growth and of course, MTI. This ecosystem has already embraced smart, agile product development to keep costs in line with early stage needs.

But we have not yet operationalized two key parts of the 21st century start-up stack.

A founder would write a business plan filled with assumptions and go pitch it. Somewhere along the way, this plan – mostly written for external audiences – went from a vision backed by a set of assumptions to something more like an internal operating plan. The catch with this shift is that companies will often scale costs prematurely before validating their assumptions about the customer and the market. Over the last 10+ years, pull marketing has met agile product development and the entire start-up process got an upgrade.

A founder would write a business plan filled with assumptions and go pitch it. Somewhere along the way, this plan – mostly written for external audiences – went from a vision backed by a set of assumptions to something more like an internal operating plan. The catch with this shift is that companies will often scale costs prematurely before validating their assumptions about the customer and the market. Over the last 10+ years, pull marketing has met agile product development and the entire start-up process got an upgrade.

In this approach, the founding team writes a plan with a heavy emphasis on surfacing the key assumptions about the business model and establishing a critical path to testing them. At each step of the way the team is learning about the market, the customer and what will give them “unfair competitive advantage”. By the time a start-up following this approach gets to launch spending levels (aka scaling up), they have dramatically reduced market adoption risk – the key risk for most start-ups in the 21st century.

In this approach, the founding team writes a plan with a heavy emphasis on surfacing the key assumptions about the business model and establishing a critical path to testing them. At each step of the way the team is learning about the market, the customer and what will give them “unfair competitive advantage”. By the time a start-up following this approach gets to launch spending levels (aka scaling up), they have dramatically reduced market adoption risk – the key risk for most start-ups in the 21st century.